The Power of Economic Growth

Just 200 years ago, all countries in the world were equally poor, meaning people the world over had identical living standards and possibilities for their lives. Then, as the industrial revolution took hold in England, and spread throughout Western Europe, the colonies, and eventually Asia, the economic conditions throughout the world radically diverged.

The life expectancy of a Japanese baby went from 35 years (1880) to 84 years (2015). In 2017, the average income of someone in the US was 3 times higher than the average person in Mexico, 10 times that of India, and 50 times that of Niger; corresponding to enormous differences in the way life is lived and experienced in these four countries.

So if everyone was equally poor 200 years ago, what happened? What explains the huge differences in wealth and living standards we see today? The answer is economic growth. A growing economy, will in the long run, leave a slower or non-growing economy far behind.

Economic Growth in a Nutshell

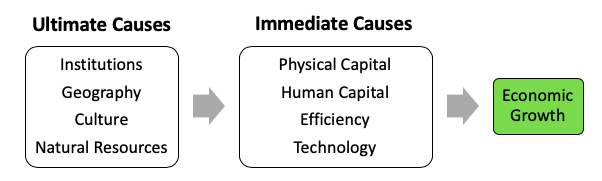

This article will leave you with an understanding of how countries try to increase their economic growth rates by increasing the four main factors of human capital, physical capital, efficiency, and technology.

Though these four directly control how much a country grows or doesn’t, we will also look at why countries continue to have different levels of these. After all, if growth is as simple as these four factors, why don’t all countries simply set their policy to get them and become rich? This question deals with the fundamental reasons why these four factors vary so much around the world. We will see that the answer lies in the ultimate causes of geography, culture, natural resources, and institutions.

Can Growth Account for the Wealth Differences Seen Today?

The average growth rate of GDP per capita (per person) in the United States has been about 2% per year over the last 150 years. Suppose we have a country that started with a wealth level of $1000 per person and then grew at 2% per year, what would its income per person be 200 years later?

Mathematically it would be: 1000*1.02*1.02*1.02… (200 times total), which can be rewritten as: 1000*(1.02200) = $52,500. That’s 52X higher level of wealth, a huge difference in living standards!

Similarly, we can compute what the wealth level would be under a couple different growth rate scenarios. As the table below shows, different levels of average growth over the past 200 years, from a starting value of $1000, can easily explain the various economic conditions we see around the world today.

| Type of Growth | Average Growth Rate | GDP Per Capita 200 Years Later | High Growth Country is Richer By: |

| High | 2% |

$ 52,485 |

– |

| Medium | 1.4% | $ 17,499 | 3X |

| Low | 0.83% | $ 5,249 | 10X |

| Almost No Growth | 0.02% | $ 1,050 | 50X |

Why Do Growth Rates Vary So Much?

But this doesn’t answer the question of why some countries grow and others don’t. After all, that’s what you’d want to know if you were the leader of a country, trying to set policies that will cause economic growth to improve.

Growth rates vary for many reasons, but before we can talk about this, it’s helpful to talk about why growth happens at all. After all, if there was no economic growth before the 1800’s, why do we have it now?

How Does Economic Growth “Happen”?

Consider the economy of 15th century Western Europe: serfs grow food, they give a portion to the lords who live off their labor, and the rest they consume with their families and trade with craftsmen for services and equipment. In order to get growth, we would need the output per person this year to be higher than output per person last year. After all, since wealth is measured in output per person, there can be no growth if the average output per person is not increasing.

So how does the economy produce more output per person this year than last year, and what all goes into this?

It comes down to two things: the output of each laborer must increase (higher productivity) or have a higher percentage of the population become laborers.

But how can the productivity of a laborer be increased?

Output Can Be Increased Via Capital

Take the example of the serf, he could save some of the output and trade it for some physical capital that would make his efforts more productive. An example is buying some cattle and a plow to enable him to grow more crops than he previously did by hand.

Another thing the serf could do is increase his human capital – i.e. improve his health and thinking skills so that he can work longer, harder, and thus produce more output than he did last year. This could be in the form of eating more food, buying medicines, learning some basic mathematics to track inventories, and so on.

Output Can Be Increased Via Technology and Efficiency Growth

There could also be growth in productivity per person for other reasons, like increased efficiency and technological advancement.

The economic system can be made more efficient by lowering taxes or allowing private land ownership. Under these changes, the serf would want to work harder and produce more, he would also want to invest in the land to make it more productive in the long run, knowing he will reap the benefits from the increased output.

Another thing that would boost output is technological advance. Suppose you are a weaver in France at the dawn of the industrial revolution in England; you are aware that England uses mechanized weaving machines that allow its users to produce 10-100X more output, if you could adopt this technology, your output would also see enormous gains.

Thus, we know that prior to the 1800s, there must have been a breakdown in the accumulation of these four factors. As discussed later, the most likely explanation is the change in institutions that occurred right around this time. They changed from extractive monarchies to more inclusive constitutional systems, featuring property rights and rule of law.

All of a sudden, the serf now has an incentive to work harder and invest a portion of their output to produce even more next period. And voila, economic growth begins.

The Solow Model Gives Intuition

We see that economic growth consists of:

- The accumulation of physical capital

- The accumulation of human capital

- Technological Growth

- Efficiency Growth

The Solow Model of Economic growth puts together all of these factors in a simple and elegant way. By assuming that output is determined by these four factors and that investment is a fixed percentage of output, it is able to explain economic growth mathematically.

Growth From Capital is Limited

Capital Stock Will Reach a Steady State Level

While we will not look at the math in this article, the implications can be considered intuitively. Growth from the accumulation of physical capital must be limited, and thus cannot be a source of sustained growth.

Since a certain part of the capital stock depreciates or wears out, a part of the annual savings must go on replenishing that depreciated capital stock, not in buying new capital stock to grow productivity. And the more capital stock is owned, the more overall depreciation there will be so that the capital stock cannot be built up indefinitely.

Eventually, the economy will reach a “steady state” level of capital, and no more gains in its stock can be had at its current level of savings.

An Example

Just consider a country that is in love with industrialization and uses, say, 20% of its annual income to invest in building factories. After some time, the wear and tear of production will require an overhaul of the factory at significant cost.

Over time if enough factories are in this poor condition, these repairs will divert most of the investment money and no new factories could be built. In fact, it could get so bad that the country wouldn’t be able to even maintain all of its existing factories, and some factories would be completely abandoned.

At a set level of savings therefore, the country would eventually reach a steady state level of capital stock.

Human Capital is Limited By The “Full Human Capital” Level

Similarly, growth from investment into human capital is also limited. If your citizens have full health and a full education, there’s really not much else additional investment into human capital can do to raise productivity.

Technological and Efficiency Growth Is Unlimited

How then do we explain the persistent growth of advanced economies like the US and Western Europe? Though it is possible they have not reached the “steady state” level of capital stock yet, the remaining factors are most important.

Intuitively this makes sense. The rich countries are also the world leaders in technological innovation, similarly, data shows that for identical industries, their production efficiency is also higher. Moreover, in an analysis of what accounts more for variation in growth rates between countries, it was found that productivity growth was twice as important as physical and human capital accumulation.1 (Economists typically bundle efficiency and technological growth into one term called: “productivity growth”.)

The Solow model, puts all this together, giving a theoretical basis for why long-term economic growth must come from productivity growth and also explaining why until the steady state level of capital is reached, economic growth can be had by simply accumulating more capital.

Ultimate Causes of Growth

While we now know the levers that control growth, what ultimately determines why some countries accumulate more capital and have higher productivity than others? As growth researchers Douglass North and Robert Thomas state:

“the factors… (innovation, economies of scale, education, capital accumulation, etc.) are not causes of growth; they are growth”2 (italics original).

Thus, it is apparent that the ultimate reasons for why economic growth happens in some countries and not in others, lie elsewhere. A list of likely ultimate reasons is geography, culture, natural resources, and institutions.

Geography and Growth

Geography can have a huge impact on an economy through several channels: agricultural productivity, labor productivity, disease burden, ability to trade, and historical influence on the institutions that were formed.

The tropics are at a disadvantage agriculturally because the heavy rainfall and frequent storms quickly wash away the nutrients contained in the soil. The absence of frost also causes there to be more competition from insects who devour crops.

The disease burden of the tropics is also significant. Consider the estimated half a billion cases of malaria that occur annually, with 60% of those occurring in the Sub-Saharan region of Africa. Similarly, countries that do not have access to waterways, have much higher costs of transportation, making it more costly to engage in trade with other countries.

Geography also is at least partially responsible for the institutions (governmental systems) that were formed in each country. China is a huge landmass but is interconnected with rivers and thus formed one giant empire for most of its history. Europe is separated by the Alps, English Channel, and the Pyrenees – influencing the formation of distinct countries. Geography’s role in forming institutions is probably its most important contribution to economic growth.

Culture and Growth

Culture can be defined as the values and beliefs that a society holds, and while it is likely that these have had an effect in shaping the resulting economic growth we see in countries around the world, it’s difficult to quantify its contribution relative to other possible explanations.

Some cultural traits that are considered particularly good for an economy include: openness to new ideas (allows innovations to be adopted), hard work, willingness to save, level of trust between people, social capital (value of social networks people have), and social capability (social qualities that allow people to take advantage of economic opportunities – like belief in cause and effect as opposed to superstition).3

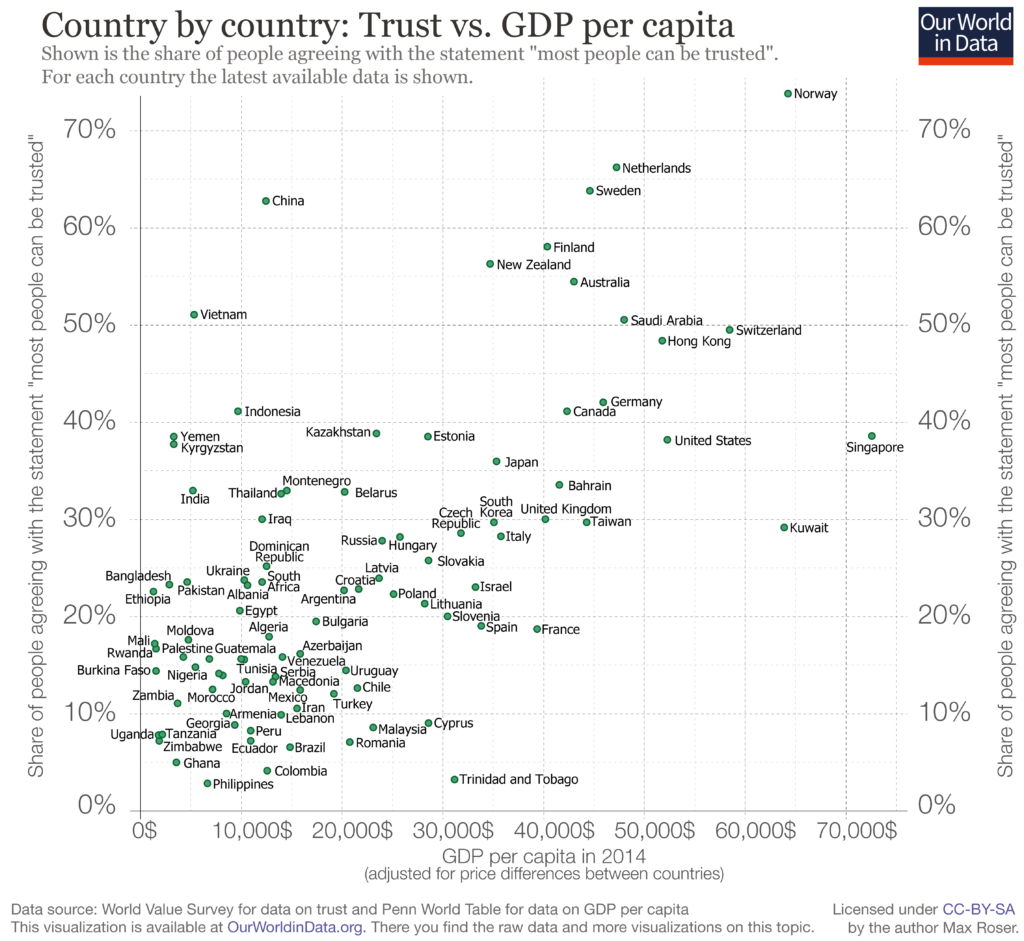

There is evidence that the possession of some of these desirable cultural characteristics is correlated with higher levels of wealth. For example, the graph below shows that the richest countries are also the ones that have the most trusting people (the vertical axis is the percentage of people who agreed with the statement “Most people can be trusted”).

Similar evidence exists for some of the other traits as well. But since culture is difficult to measure, more work remains to be done here.

Natural Resources and Growth

Not So Important

Contrary to our intuition, natural resources appear to have only a weak effect on economic growth. Countries for which natural capital (total value of natural resources) data is available, finds only a slightly positive relationship between GDP per capita and Natural Capital per capita (meaning more wealthy countries generally have more natural capital), but many exceptions exist.

For example, Switzerland and Japan have very low natural capital per person, yet have among the highest GDPs. The reason for this is simple: natural resources can be traded, and if a country can provide other value via its economy, it can receive the resources it lacks through trade.

Having Resources Can Be a Curse If the Institutions Are Extractive

Additionally, there are many cases in which the possession of vast resources actually leads a country into greater poverty – this is referred to as the “resource curse”. Although this is not because of the abundant resources themselves but because of the extractive institutions these countries have.

The leaders are focused on maintaining power and wealth from the extraction of resources, not on investing in the people and growing the economy. The lucrative prize of absolute power and wealth also leads to infighting and instability as elites jockey for control of the country, impoverishing the country still further.

Institutions and Growth

Institutions can be thought of as the economic system created by the government, the “rules of the game” by which economic activity is conducted. Some countries have “inclusive institutions”, where the institutions are designed fairly and equitably for all the people of a nation.

The opposite is “extractive institutions” where only the elites have a say in the government. Naturally the laws will benefit only them, at the expense of the rest of the nation. We would expect inclusive institutions to be good for growth, and extractive institutions to be bad for growth.

Perhaps the greatest evidence for this is “natural experiments” where culture, geography, and natural resources are identical and only institutions differ. The evidence we have in these situations (think North and South Korea, East and West Germany) indicate that institutions alone are already enough to explain wealth and poverty.

Moreover, poor countries generally do a worse job of maintaining the rule of law and have higher levels of corruption. This is pretty good evidence that institutions are the primary channel through which economic growth is created. A previous article discusses this in more detail.

What About Population Growth?

Population growth rate also plays a role in explaining economic growth. A faster growing population, on the one hand means more inventors, laborers, and scientists – which should lead to more productivity and technological growth.

On the other hand, a new population, means more money must be invested into capital just to maintain the previous level of capital per person, in addition to the human capital investments required.

This is referred to as the “capital dilution” effect of population growth and the Solow Model discussed earlier, predicts that with all other conditions held equal (productivity level, capital share, depreciation rate, etc), a country with a 1% higher population growth rate will have an income level about 10% lower.

So we see that there are positive and negative effects of population growth rate on the economic growth rate. But there is a clear relationship in the data that richer countries have a lower population growth rate than do poorer countries. This doesn’t necessarily mean that countries are wealthier because they have less kids. Instead, there is evidence that the relationship goes both ways: as people become wealthier they tend to want less kids.

Summary of How Economic Growth Works

We Have a Rough Understanding, But Details Are Needed

In this article, we have looked at how economic growth can be broken down into the factors of production: physical capital and human capital, in addition to productivity, which itself consists of the efficiency of the economy and its technological level.

We have discussed how the Solow Model provides a mathematical explanation for how the accumulation of these factors would affect growth. But though there is a theoretical basis, we also wanted to answer why the levels of these factors vary so much in countries around the world.

To analyze this, we looked at four possible ultimate factors: geography, culture, natural resources, and institutions. From our discussion, while it is plausible that all have an impact on economic growth, if ranked based on what we know today, the most important would be the institutions a nation possesses.

Though we do have a rough idea, many details remain to be worked out to reveal more precisely the mechanisms by which economic growth works.

[expand title=”Sources”]

- See p205 of Economic Growth by David N. Weil, 2nd Edition

- Cited on p388 of Handbook of Economic Growth, Vol 1A

- See p419 of Economic Growth by David N. Weil, 2nd Edition

[/expand]